Christmas Under German Occupation – Witold Pilecki: Part 1

Continuing our series of blog posts about Christmas under German occupation—

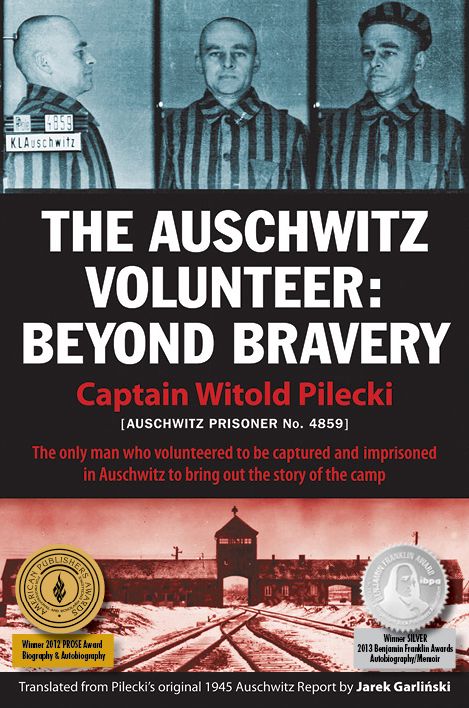

In September 1940, Polish Army officer Witold Pilecki walked into a German street round-up in Warsaw…and became Auschwitz Prisoner No. 4859. Pilecki had volunteered for a potentially suicidal secret undercover mission for the Polish Underground—to get himself arrested by the Germans and sent to Auschwitz as a prisoner. His mission: smuggle out intelligence about this new German concentration camp, and build a resistance organization among prisoners with the ultimate goal of liberating the camp.

Barely surviving nearly three years of starvation, disease and brutality, Pilecki accomplished his mission before escaping in April 1943. His clandestine intelligence reports from the camp, received by the Allies as early as 1941, were among the earliest, including the full horrors of daily life inside the camp, the killing of Soviet soldiers taking as prisoners of war, the building of the gas chambers and mass extermination of Jews brought to the camp.

Auschwitz was originally a concentration camp for Polish political prisoners, and only later evolved into a death camp for the Jews of Europe.

The Germans used prisoners as slave labor to expand the camp well beyond its initial use as prewar Polish military barracks, constructing more buildings to house prisoners and camp functions, numerous sub-camps such as Birkenau and Monowice, gas chambers, and heavy industry plants for the German war effort. Prisoners were also used to help run the camp. The key to survival was to get an indoor job — in the kitchens, the hospital, administrative offices, carpenter and other craft shops, etc. Pilecki’s resistance organization helped its members to do just that, giving them at least a better chance at surviving than those forced to work outdoors all year long in all weather.

We published Pilecki’s most comprehensive report on Auschwitz, written in 1945 and suppressed by the postwar Polish communist regime for nearly fifty years, in English for the first time, under the title The Auschwitz Volunteer: Beyond Bravery.

We published Pilecki’s most comprehensive report on Auschwitz, written in 1945 and suppressed by the postwar Polish communist regime for nearly fifty years, in English for the first time, under the title The Auschwitz Volunteer: Beyond Bravery.

Although conditions were difficult for all Poles under the German occupation, those imprisoned at Auschwitz faced a truly hellish existence. Most did not survive. Yet even under such unspeakable conditions, the human spirit sought solace in some form of Christmas rituals.

Excerpts from The Auschwitz Volunteer: Beyond Bravery:

Christmas 1940

p. 49:

Kazik (in Block 17) once told us: “The worst is getting through the first year.” Some smiled politely. “A year? We’ll be home by Christmas. The Germans won’t last! England, etc., etc.!” (Sławek Szpakowski) … filled others with foreboding. “A year? Who could survive a year here?” When one played blind man’s bluff with death on a daily basis. . . not today. . . perhaps tomorrow!—and a day sometimes seemed as long as a year.

pp. 72–73:

Ah! . . . the crisis of hunger arrives in all its different degrees.

There were times when one felt oneself capable of cutting off a piece from a corpse lying outside the hospital.

It was then, just before Christmas, that they began to issue us barley gruel in the morning instead of “tea,” which was a great blessing, but I do not know who was responsible. (It continued until the spring.)

A couple of beautifully lit Christmas trees were put up in the camp for Christmas.

In the evening the kapos laid two häftlings [prisoners] on two benches under the trees and gave them 25 strokes on that part of the body which out in the free world has been called soft.

This was supposed to be a German joke….

pp. 79–80:

For Christmas of 1940 inmates were for the first time allowed to receive parcels from their families.

But not food parcels, oh no!

We were not allowed to receive food parcels for fear we might have it too easy.

The first parcel arrived at Auschwitz. It was a clothes parcel, containing a number of previously specified items: a sweater, a scarf, gloves, ear muffs, socks.

Nothing more could be sent. Someone’s parcel contained underwear—it went to the sack in the effektenkammer [storeroom for inmates’ personal belongings] with the inmate’s number and stayed there.

That is how it was then.

We later managed to get into everything, with the help of fellows in the know.

There was just one parcel, one a year, at Christmas, with no food, but still valuable because of the warm clothes, and precious because it came from home.

Over Christmas, Westrych and the carpenters’ shop kapo [a “trusted” prisoner chosen by the Germans to be a supervisor] managed to wangle for the carpenters some additional cooking pots of an excellent stew from the SS kitchen, and the arriving carpenters were in for a treat in the shop.

These pots came around a number of times and also later, brought in secretly by the SS who received money collected from us by Westrych.

Continued in Christmas Under German Occupation—Witold Pilecki: Part 2….

No comment yet, add your voice below!