Christmas Under Soviet Occupation – Stefan Waydenfeld

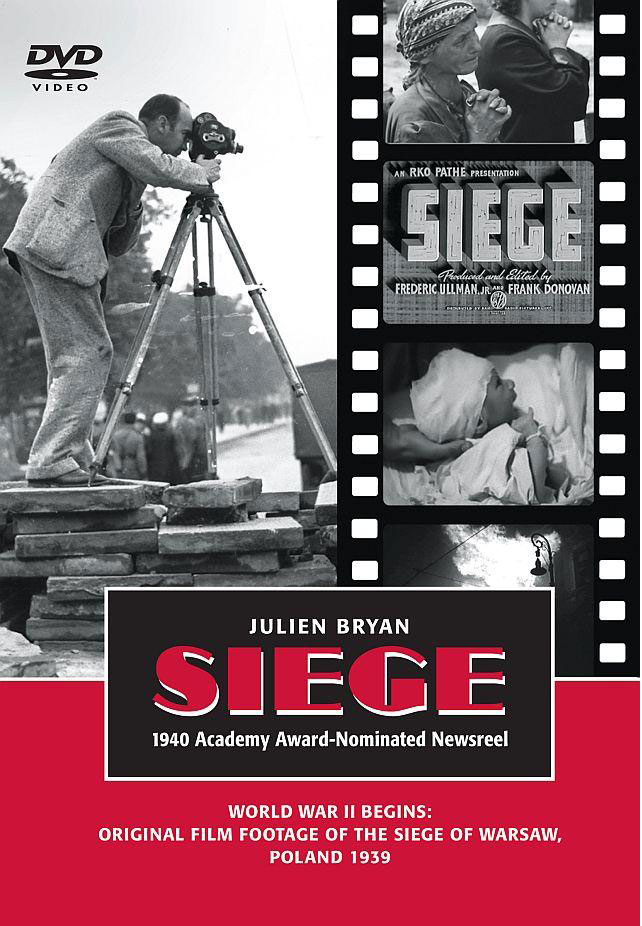

World War II broke out on September 1, 1939, when Germany invaded Poland from the west. On September 17, 1939, the Soviet Union invaded Poland from the east. These two enemies divided Poland between them, with the Germans occupying most of the central and western part of the country, and the Soviets occupying the eastern part.

World War II broke out on September 1, 1939, when Germany invaded Poland from the west. On September 17, 1939, the Soviet Union invaded Poland from the east. These two enemies divided Poland between them, with the Germans occupying most of the central and western part of the country, and the Soviets occupying the eastern part.

Christmas was treated very differently in German- and Soviet-occupied Poland. The Germans recognized Christmas and generally tolerated Poles celebrating the holiday. But for the Soviets, Christmas did not exist. Indeed, in the Soviet Union, the practice of all religions was forbidden. Karl Marx, whose philosophy was the major foundation of communism in the Soviet Union, famously said “religion is the opiate of the masses.”

When the war started, Stefan Waydenfeld was only 14 years old but, as he says, “strong and tall for my age.” Within the first week of war, the Polish Army began retreating eastwards in the face of the rapid German advance. The Polish government quickly called for all able-bodied men to join the fight. Young Waydenfeld left his home in Otwock, a suburb of Warsaw, to help defend his country. His father had previously been mobilized. After the Soviet invasion, Waydenfeld and his father, and eventually his mother who joined them, began an unexpected odyssey that lasted many years.

In December 1939, the family settled briefly in the Soviet-occupied city of Pińsk, but in late June 1940 were routed by Soviet soldiers and deported by cattle car to a forced labor camp in the frozen wasteland of Kvasha, Siberia. Forced to work under harsh conditions, they barely survived. When Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, the Poles who had been sent to Siberia were freed.

In December 1939, the family settled briefly in the Soviet-occupied city of Pińsk, but in late June 1940 were routed by Soviet soldiers and deported by cattle car to a forced labor camp in the frozen wasteland of Kvasha, Siberia. Forced to work under harsh conditions, they barely survived. When Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, the Poles who had been sent to Siberia were freed.

They made their way across the Soviet Union any way they could — their goal: to join the new Polish army being formed in the Soviet Union under command of General Władysław Anders. Along the way, the Waydenfeld family settled briefly in Chirakchi, Uzbekistan, still within the Soviet Union.

Excerpts from The Ice Road: An Epic Journey from the Stalinist Labor Camps to Freedom by Stefan Waydenfeld:

Excerpts from The Ice Road: An Epic Journey from the Stalinist Labor Camps to Freedom by Stefan Waydenfeld:

Chapter 5, “The Lesser Evil”

pp. 53–54:

Mrs. Margulis, our landlady, was a widow and lived alone in a two-storey house. She let us have the ground floor. Father was pleased: ‘It is also only ten to fifteen minutes’ walk from the main Pińsk secondary school. Better enrol, Stefanku, even before Christmas.’

‘Christianity is out, Dad,’ I pointed out. ‘It’s now called a “short winter break.” Something to do with Grandfather Frost.’

Chapter 9, “The Ice Road”

pp. 131; 141–142:

The Kvasha ice road has remained forever my idea of purgatory; it was far too cold for hell.

On a more practical level it was a primitive method of timber transportation [during the winter]….

Days off in Kvasha were few and far between….

We had a day off on 7 November, the anniversary of the October Revolution. And then again we had a free New Year’s Day, January 1941, and then one free Sunday in March.

Chapter 16, “Chirakchi—A Respite”

p. 283:

We never went hungry in Chirakchi. Life began to look up.

‘It’s school for you, Stefan,’ said Father one day. ‘There is a ten-year school in town. You could start in the new year.’ Predictably, Christmas was taboo in the USSR, but schools had a short winter break around the New Year; transformed into the festival of Dyed Moroz, Grandfather Frost.

No comment yet, add your voice below!