V-2 Rocket Smuggled Out of Occupied Poland

Today is the 80th anniversary of a coup by Polish Underground Intelligence and British Special Operations Executive (SOE).

On July 25, 1944, a Dakota transport plane landed secretly at night in German-occupied Poland and loaded up with parts of a new German “wonder weapon” — the V-2 rocket — along with Polish experts’ analyses, to send back to Britain for further analysis.

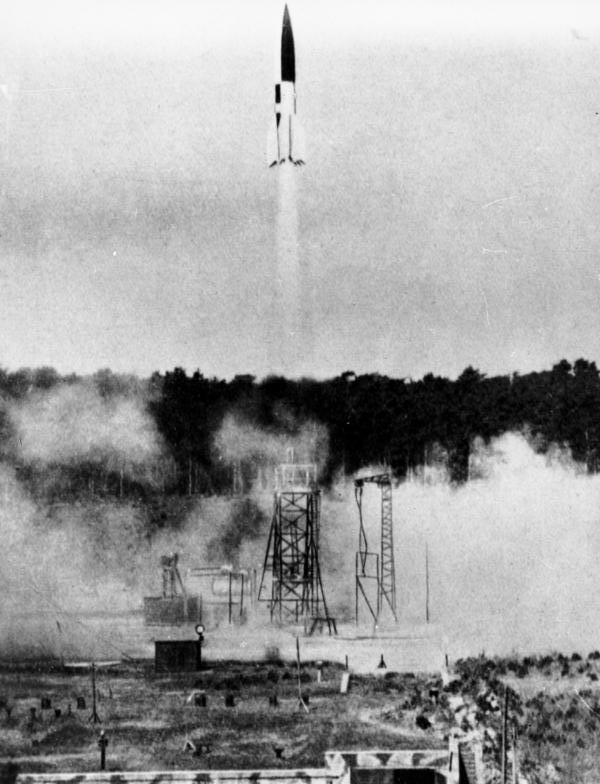

The V-2 rocket was the world’s first ballistic weapon. With the Germans being pressured on both the Western and Eastern Fronts after D-Day, Hitler hoped that this new weapon would turn the tide of the war against the Western Allies. The Germans were testing V-2 rockets in Poland from a missile launch site near Blizna, northwest of Rzeszów. The Polish Underground made a concerted effort to recover and analyze the rockets from failed tests.

This was only the third time that an SOE plane had landed in and taken off from German-occupied Poland (the so-called “Bridge” or, in Polish “Most,” flights organized by SOE). All prior flights had been flyovers to release parachutists (mostly Cichociemni, the “Unseen and Silent” Polish special forces parachutists) and supplies. Landing and taking off in any German-occupied territory was beyond risky.

The Dakota took off from the Allied base at Brindisi, Italy at 8 p.m. on July 25, 1944. The crew was British, with the exception of the navigator, Flight Lieutenant Kazimierz Szrajer, who was in command. The plane carried 19 suitcases full of special equipment and four Polish military passengers.

The SOE transport landed at the Polish Underground landing site ‘Motyl’ (‘Butterfly’). The suitcases and passengers were offloaded, while a westbound group boarded in a predetermined order of priority in case the plane could not take the full load: first and foremost, the V-2 rocket parts; secondly, Jerzy Chmielewski ‘Raphael,’ who carried a detailed report on the secret weapon and was ready to supplement it from his unfailing memory; followed by four passengers in order of importance.

The plane had to take off well before daylight. Unfortunately, when it tried to take off, the plane’s wheels stuck in the mud. Twice everything was unloaded and efforts were made to provide traction for the wheels — first with straw, and finally with planks. If the plane could not take off, it was to be destroyed by dousing it in gasoline and burning it. The aircrew was actually splashing gasoline on the landing gear when the planks were tried … and succeeded, enabling the plane to take off.

The Dakota arrived back in Brindisi at 5:50 a.m. on the 26th. After a detour the following day to Rabat in Morocco to deliver three of the passengers, the V-2 rocket was safely delivered in London on July 28, 1944.

The Germans sent the first V-2 to London on September 18, 1944. By that time, such methods of defense as were possible had been organized, as well as the launching sites having been pushed back by the advance of Allied armies.